Abortion Four Times Deadlier Than Childbirth

New Studies Unmask High Maternal Death Rates From Abortion

Abortion advocates, relying on inaccurate maternal death data in the United States, routinely claim that a woman’s risk of dying from childbirth is six, ten, or even twelve times higher than the risk of death from abortion.

In contrast, abortion critics have long contended that the statistics relied upon for maternal mortality calculations have been distorted and that the broader claim that “abortion is many times safer than childbirth” completely ignores high rates of other physical and psychological complications associated with abortion. Now a recent, unimpeachable study of pregnancy-associated deaths in Finland has shown that the risk of dying within a year after an abortion is several times higher than the risk of dying after miscarriage or childbirth.(1)

This well-designed record-based study is from STAKES, the statistical analysis unit of Finland’s National Research and Development Center for Welfare and Health. In an effort to evaluate the accuracy of maternal death reports, STAKES researchers pulled the death certificate records for all the women of reproductive age (15-49) who died between 1987 and 1994–a total of 9,192 women. They then culled through the national health care data base to identify any pregnancy-related events for each of these women in the 12 months prior to their deaths.

Since Finland has socialized medical care, these records are very accurate and complete. In this fashion, the STAKES researchers identified 281 women who had died within a year of their last pregnancy. The unadjusted mortality rate per 100,000 cases was 27 for women who had given birth, 48 for women who had miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies, and 101 for women who had abortions.

cases was 27 for women who had given birth, 48 for women who had miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies, and 101 for women who had abortions.

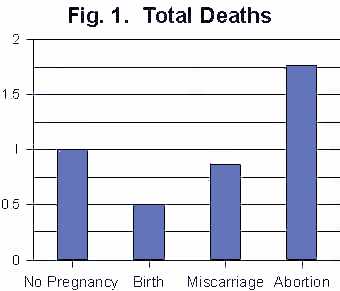

The researchers then calculated the age-adjusted odds ratio of death, using the death rate of women who had not been pregnant as the standard equal to one. Table 1 shows that the age-adjusted odds ratio of women dying in the year they give birth as being half that of women who are not pregnant, whereas women who have abortions are 76 percent more likely to die in the year following abortion compared to non-pregnant women. Compared to women who carry to term, women who abort are 3.5 times more likely to die within a year.

Such figures are always subject to statistical variation from year to year, country to country, study to study. For this reason, the researchers also reported what is known as “95 percent confidence intervals.” This means that the available data indicates that 95 percent of all similar studies would report a finding within a specified range around the actual reported figure.

For example, the .50 odds ratio for childbirth has a confidence interval of .32 to .78. In other words, it is probable that 95 percent of the time, the odds ratio of death following childbirth will be found to be between 32 percent and 78 percent of the non-pregnant woman rate. The 95 percent confidence interval for the odds ratio of death following abortion was reported to be 1.27 to 2.42 of the annual rate for non-pregnant women.

Deaths from Suicide

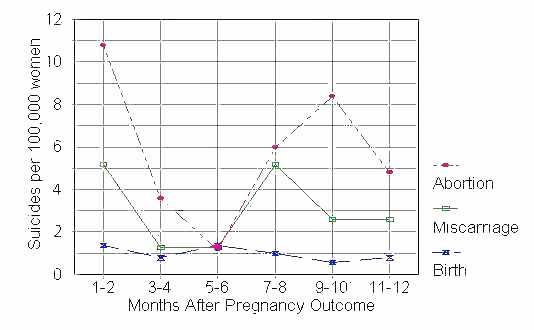

Using a subset of the same data, STAKES researchers had previously reported that the risk of death from suicide within the year of an abortion was more than seven times higher than the risk of suicide within a year of childbirth.(2) Two of these suicides were also connected with infanticide. Examples of post-abortion suicide/infanticide attempts have also been documented in the United States.(3)

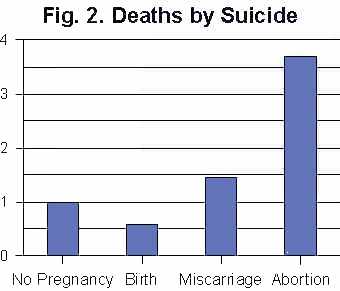

The same finding was reported in STAKES’ more recent study. Among the 281 women who died within a year of their last pregnancy, 77 (27 percent) had committed suicide. Figure 2 shows the age-adjusted odds ratio for suicide for the three pregnancy groups compared to the “no pregnancy” control group.

Notably, the risk of suicide following a birth was about half that of the general population of women. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown that an undisturbed pregnancy actually reduces the risk of suicide.(4)

Abortion, on the other hand, is clearly linked to a dramatic increase in suicide risk. This statistical finding is corroborated by interview-based studies which have consistently shown extraordinarily high levels of suicidal ideation (30-55 percent) and reports of suicide attempts (7-30 percent) among women who have had an abortion.(5) In many of these studies, the women interviewed have explicitly described the abortion as the cause of their suicidal impulses.

The original publication of the STAKES suicide data prompted researchers at the South Glamorgan (population 408,000) Health Authority in Great Britain to examine their own data on admissions for suicide attempts both before and after pregnancy events. They found that among those who aborted, there was a shift from a roughly “normal” suicide attempt rate before the abortion to a significantly higher suicide attempt rate after the abortion. After their pregnancies, there were 8.1 suicide attempts per thousand women among those who had abortions, compared to only 1.9 suicide attempts among those who gave birth. The higher rate of suicide attempts subsequent to abortion was particularly evident among women under 30 years of age.

As in the STAKES sample, birth was associated with a significantly lower risk of suicide attempts. The South Glamorgan researchers concluded that their data did not support the view that suicide after an abortion was predicated on prior poor mental health, at least as measured by prior suicide attempts. Instead, “the increased risk of suicide after an induced abortion may therefore be a consequence of the procedure itself.”(6)

Interpretation of these statistical studies is aided by numerous publications describing individual cases of completed suicide following abortion.(7) In many cases, the attempted or completed suicides have been intentionally or subconsciously timed to coincide with the anniversary date of the abortion or the expected due date of the aborted child.(8) Suicide attempts among male partners following abortion have also been reported.(9)

Teens are generally at higher risk for both suicide and abortion. In a survey of teenaged girls, researchers at the University of Minnesota found that the rate of attempted suicide in the six months prior to the study increased ten fold–from 0.4 percent for girls who had not aborted during that time period to 4 percent for teens who had aborted in the previous six months.(10) Other studies also suggest that the risk of suicide after an abortion may be higher for women with a prior history of psychological disturbances or suicidal tendencies.(11)

It is also worth noting the suicide rate among women in China is the highest in the world. Indeed, 56 percent of all female suicides occur in China, mostly among young rural women.(12) It is also the only country where more women die from suicide than men. For women under 45, the suicide rate is twice as high as that of Chinese men. Government officials are reported to be at a loss for an explanation.

Traditionally, Chinese families placed a high value on large families, especially in rural communities. But after the death of Mao Tse-Tung, who also valued large families, China instituted its brutal one child policy. This population control effort, encouraged by governments and family planning organizations from the West, has required the widespread use of abortion–including forced abortion–and infanticide, especially of female babies. Given the known link between abortion and suicide, can there be any doubt that maternally-oriented Chinese women who are coerced by their families and communities to participate in these atrocities are more likely to commit suicide?

Deaths from Accidents

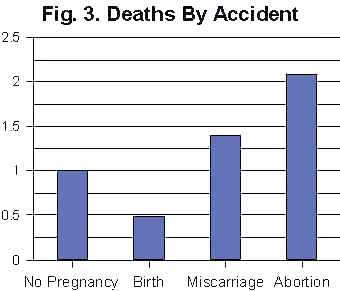

In this most recent study from Finland, the STAKES researchers also reported that the risk of death from accidents was over four times higher for women who had aborted in the year prior to their deaths than for women who had carried to term. Of the 281 women who died within a year of their last pregnancy, 57 (20 percent) died from injuries attributed to accidents.

Once again, giving birth had a protective effect. Women who had borne children had half the risk of suffering a fatal accident compared to the general population. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 3, women who aborted were more than twice as likely to die from a fatal accident than women in the general population.

This finding suggests that women with newborn children are probably more careful to avoid risks which could endanger them or their children. Conversely, women who have had an abortion are apparently more prone to taking risks that could endanger their lives.

This data is consistent with at least two other studies that have found that women who abort are more likely to be treated for accident-related injuries in the year following their abortions.

In a study of government-funded medical programs in Canada, researchers found that women who had undergone an abortion in the previous year were treated for mental disorders 41 percent more often than postpartum women, and 25 percent more often for injuries or conditions resulting from violence.(13)

Similarly, a study of Medicaid payments in Virginia found that women who had state-funded abortions had 62 percent more subsequent mental health claims (resulting in 43 percent higher costs) and 12 percent more claims for treatments related to accidents (resulting in 52 percent higher costs) compared to a case matched sample of women covered by Medicaid who had not had a state-funded abortion.(14)

It is quite likely that some of these deaths which were classified as accidental may have in fact been suicides. Reports of post-abortive women deliberately crashing their automobiles, often in a drunken state, in an attempt to kill themselves have been reported by both post-abortion counselors and in the published literature.(15)

It is also likely that many of these deaths are simply related to heightened risk-taking behavior among post-abortive women. This may occur simply because some women care less whether they live or die after an abortion. Other women may seek to “self-medicate” a sense of depression with the adrenalin rush that often comes with taking risks. In addition, heavier drinking and substance abuse are well-documented aftereffects of abortion, both of which increase a person’s risk of fatal accidents.(16)

Deaths from Homicide

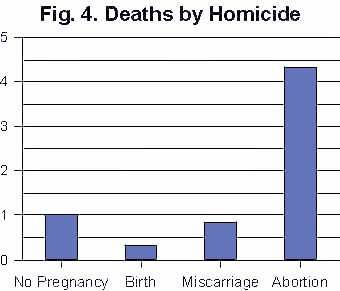

The STAKES study also found that 14 (5 percent) of the 281 women were killed by another person. Most of these deaths occurred among women who had undergone an abortion. As shown in Figure 4, the risk of dying from homicide for post-abortive women was more than four times greater than the risk of homicide among the general population. This finding , especially when combined with the suicide and accident figures, once again reinforces the conclusion that women who abort are more likely to engage in risk-taking behavior.

, especially when combined with the suicide and accident figures, once again reinforces the conclusion that women who abort are more likely to engage in risk-taking behavior.

An Elliot Institute survey of 256 post-abortive women found that nearly 60 percent stated that they began to lose their temper more easily after their abortions, with 48 percent saying they also became more violent when angered. Increased tendencies toward anger and violence after abortion were also significantly associated with substance abuse and higher suicidal tendencies.(17)

In other words, women who were more prone to anger were also more prone to “giving up” on life. This is a dangerous combination which can more easily lead to fatal confrontations with others.

In the STAKES study, an additional 6 deaths that were due to traumatic physical injuries were listed as “unclear violent deaths.” In these cases, the researchers could not make a determination of whether the cause of death was due to accident, suicide, or homicide.

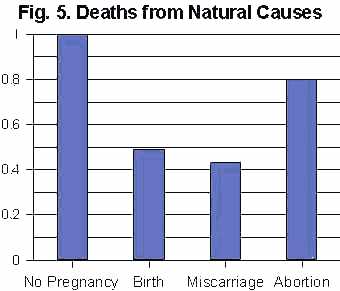

Deaths from Natural Causes

Of the 281 deaths, 127 (45 percent) were attributed to natural causes. As seen in Figure 5, the age adjusted odds ratio of dying from natural causes within a year following any outcome of pregnancy is less than the odds ratio of dying for non-pregnant women.

The obvious implication of this finding is that women  who are capable of becoming pregnant are simply healthier and less likely to die of natural causes than women who cannot or do not become pregnant. In other words, women who are most likely to die from a natural physical ailment are less likely to have been pregnant in the last year of their lives.

who are capable of becoming pregnant are simply healthier and less likely to die of natural causes than women who cannot or do not become pregnant. In other words, women who are most likely to die from a natural physical ailment are less likely to have been pregnant in the last year of their lives.

Comparing abortion to birth, however, we once again see that the risk of death from natural causes was significantly higher (60 percent higher in this sample) for women who had an induced abortion in the prior year compared to those who carried to term or had a natural pregnancy loss.

One possible explanation would be that the women who died after an abortion were already in ill health before the abortions and sought the abortion to protect their health. But this hypothesis was rejected by the STAKES researchers when an examination of abortion registry records showed that only a single woman in this group had her abortion for reasons of maternal health.(18) The STAKES data would appear to support the view that induced abortion produces an unnatural physical and psychological stress on women that can result in a negative impact on their general health.

This theory is also supported by a 1984 study that examined the amount of health care sought by women during a year before and a year after their induced abortions. The researchers found that on average, there was an 80 percent increase in the number of doctor visits and a 180 percent increase in doctor visits for psychosocial reasons after abortion.(19)

Ten years later, another study of 1,428 patients chosen at random from their office visits to 69 general practitioners found that pregnancy loss, especially abortion, was significantly associated with a lower assessment of general health.(20) The more pregnancy losses a woman had suffered, the more negative her general health score. In addition, loss of a woman’s most recent pregnancy was more strongly associated with lower health than were losses followed by successful deliveries.

While the researchers found that miscarriage was also associated with a lower health score, induced abortion was more strongly associated with a lower health assessment and more frequently identified by women as the cause of their reduced level of health. More than 20 percent of the women participating in the study expressed a moderate to strong need for professional help to resolve their loss.

From this data, Dr. Philip Ney, who led the research team, concluded that acute or pathological grief after the loss of an unborn child, whether by miscarriage or abortion, has a detrimental effect on the psychological and physical health of some women.

Ney proposed several possible reasons for this: (1) depression has been linked to suppressed immune responses, (2) psychological conflict consumes energy that would otherwise be spent in more healthy ways, and (3) prolonged or unresolved mourning may distract the woman from taking care of other health needs or confuse her interpretation of situations and events. In addition to these factors, abortion has been linked to sleeping disorders, eating disorders, and substance abuse, all of which can have a direct negative impact on a woman’s health.

Conclusions

The STAKES study of pregnancy-associated deaths is beyond reproach. It is a record-based study in a country with centralized medical records. While a small number of women who died during the period investigated may have had births or abortions outside of Finland which would not have been identified in the records, there is no reason to believe these few cases would have altered these dramatic findings.

Clearly, the odds of a woman dying within a year of having an abortion are significantly higher than for women who carry to term or have a natural miscarriage. This holds true both for deaths from natural causes and deaths from suicide, accidents, or homicide. In addition, the study underscores the difficulty in reliably defining and identifying maternal deaths. Only 22 percent of the death certificates examined had any mention of the woman’s recent pregnancy.

Unfortunately, there is often no clear way of determining when there is any causal connection between a death and a previous pregnancy, birth, miscarriage, or abortion. According to the lead author of the STAKES study, Mika Gissler, in maternal health reports throughout the world, “[t]here is no consensus concerning which cases should be included as maternal deaths. Problematic are, for example, some cancers, stroke, asthma, liver cirrhosis, pneumonia with influenza, anorexia nervosa, and many violent deaths, such as suicide, homicide, and accidents.”(21)

By stepping back from a predefined notion of what constitutes a pregnancy-related death, the STAKES team has shown that deaths among women following a pregnancy cannot easily be tracked when a study is based purely on short-term post-operative recovery. This is particularly true following an abortion. Maternal deaths after an abortion are seldom identified as such unless the death occurs on the operating table, if even then (see accompanying article on page 5). By examining all death certificates and all pregnancy events in the prior year, the STAKES team avoided the basic problem of pre-defining what deaths will be included or excluded in maternal mortality reports.

Even this study, however, has shortcomings. The most obvious limitation is that the researchers examined only a single year of the reproductive history of women who had died during the study period. Since suicide attempts are often associated with the anniversary date of the abortion, some portion of deaths from suicide or accidents that occurred slightly over one year after a prior abortion were probably missed.

As seen in Figure 6, the distribution of suicides by month following the pregnancy event indicate an increased level of suicides at seven to ten months following an abortion. This may correspond to a negative anniversary reaction related to the expected due date of the aborted child. A similar spike is seen among women who had miscarriages, though it peaks a couple of months earlier, perhaps because the miscarriages generally occurred further along in gestation than the abortions.

Figure 6: Suicide Rate by Month After Pregnancy Event

Another disadvantage of the one-year limit on the STAKES data set is that it does not reveal how long the protective effect of birth extends, or conversely, how long the odds ratio of death for those who abort remains elevated. A study spanning a longer period of time would be needed to identify these longer term effects.

Finally, the STAKES study does not shed any light on whether or not women who died from suicide or risk-taking behavior after an abortion were already self-destructive before their abortions. It is probable that many were. Women with a propensity for risk-taking would be more likely to become pregnant and perhaps more likely to choose abortion. In such cases, while abortion may not be the underlying cause of their problems, it probably contributed to their psychological deterioration and was a contributing cause of their death.

On the other hand, it is also clear from other studies that many women who were not previously self-destructive become so as a direct result of their traumatic abortion experience. Whether this latter group represents a major or minor portion of those who died in the STAKES sample is unknown.

Additional insights could be gained by looking back over several more years of the women’s medical records. It is likely that prior suicide attempts, a high incidence of treatment for accidents, prior psychological treatments, and other prior pregnancy losses would all be associated with an increased risk of subsequent death by suicide, homicide, or accident.

Abortion advocates will naturally argue that abortion did not “cause” any of these deaths, but rather that these women were simply self-destructive or ill beforehand and would have died anyway. This is a flimsy argument, since clearly this same data shows that giving birth has a protective effect. Even women who committed suicide after giving birth waited until after their children were born to take their own lives.

It is quite probable that the best way to help a self-destructive woman to change her life, and value her own life, is to encourage her to cherish the life of her unborn child. Conversely, it is clear that aiding and encouraging a self-destructive woman to undergo an abortion is likely to aggravate her self-destructive tendencies.

These findings underscore the importance of holding abortion clinics liable for screening women who are seeking an abortion for a history of suicide, self-destructive behavior, and psychological instability. The failure to screen for these risk factors is clearly gross negligence. In addition, when abortion clinic counselors falsely reassure women that abortion is safer than childbirth, they should be held accountable for false and deceptive business practices.

Originally published in The Post-Abortion Review, 8(2), April-June 2000. Copyright 2000, Elliot Institute.

- Abortion Four Times Deadlier Than Childbirth

- Informed Consent Booklets Hide True Risks of Abortion

- Two Senseless Deaths: The Long Road to Recovery

- Abortionists Are Not Held Accountable for Mistakes

- Deaths associated with abortion compared to childbirth: a review of new and old data and the medical and legal implications (The Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy)

- Higher Death Rates After Abortion Found in U.S., Finland, and Denmark

- Multiple Abortions Increase Risk of Maternal Death: New Study

Citations

1. Gissler, M., et. al., “Pregnancy-associated deaths in Finland 1987-1994 — definition problems and benefits of record linkage,” Acta Obsetricia et Gynecolgica Scandinavica 76:651-657 (1997).

2. Mika Gissler, Elina Hemminki, Jouko Lonnqvist, “Suicides after pregnancy in Finland: 1987-94: register linkage study” British Medical Journal 313:1431-4, 1996.

3. McFadden, A., “The Link Between Abortion and Child Abuse,” Family Resources Center News (January 1998) 20.

4. S. J. Drower, & E. S. Nash, “Therapeutic Abortion on Psychiatric Grounds,” South African Medical Journal 54:604-608, Oct. 7, 1978; B. Jansson, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia 41:87, 1965.

5. David Reardon, “Psychological Reactions Reported After Abortion,” The Post-Abortion Review, 2(3):4-8, Fall 1994; Anne C. Speckhard, The Psychological Aspects of Stress Following Abortion (Kansas City: Sheed & Ward, 1987); Vincent Rue, “Traumagenic Aspects of Elective Abortion: Preliminary Findings from an International Study” Healing Visions Conference, June 22, 1996.

6. Christopher L. Morgan, et. al., “Mental health may deteriorate as a direct effect of induced abortion,” letters section, BMJ 314:902, 22 March, 1997.

7. E. Joanne Angelo, Psychiatric Sequelae of Abortion: The Many Faces of Post-Abortion Grief,” Linacre Quarterly 59:69-80, May 1992; David Grimes, “Second-Trimester Abortions in the United States, Family Planning Perspectives 16(6):260; Myre Sim and Robert Neisser, “Post-Abortive Psychoses,” The Psychological Aspects of Abortion, ed. D. Mall and W.F. Watts, (Washington D.C.: University Publications of America, 1979).

8. Carl Tischler, “Adolescent Suicide Attempts Following Elective Abortion,” Pediatrics 68(5):670, 1981.

9. “Psychopathological Effects of Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy on the Father Called Up for Military Service,” Psychologie Medicale 14(8):1187-1189, June 1982; Angelo, op. cit.

10. B. Garfinkle, H. Hoberman, J. Parsons and J. Walker, “Stress, Depression and Suicide: A Study of Adolescents in Minnesota” (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Extension Service, 1986)

11. Esther R. Greenglass, “Therapeutic Abortion and Psychiatric Disturbance in Canadian Women,” Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 21(7):453-460, 1976; Helen Houston & Lionel Jacobson, “Overdose and Termination of Pregnancy: An Important Association?” British Journal of General Practice, 46:737-738, 1996.

12. Elizabeth Rosenthal, “Women’s Suicides Reveal China’s Bitter Roots: Nation Starts to Confront World’s Highest Rate,” The New York Times, Sunday January 24, 1999, p. 1, 8.

13. R.F. Badgley, D.F. Caron, M.G. Powell, Report of the Committee on the Abortion Law, Minister of Supply and Services, Ottawa, 1977:313-319.

14. Jeff Nelson,”Data Request from Delegate Marshall” Interagency Memorandum, Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, Mar. 21, 1997.

15. Carl Tischler, “Adolescent Suicide Attempts Following Elective Abortion,” Pediatrics 68(5):670, 1981; E. Joanne Angelo, Psychiatric Sequelae of Abortion: The Many Faces of Post-Abortion Grief,” Linacre Quarterly 59:69-80, May 1992.

16. D.C. Reardon and P.G. Ney, “Abortion and Subsequent Substance Abuse” Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 26(1):61-75.

17. David Reardon, “Psychological Reactions Reported After Abortion,” The Post-Abortion Review, 2(3):4-8, Fall 1994

18. Personal communication with Mika Gissler, March 8, 2000.

19. D. Berkeley, P.L. Humphreys, and D. Davidson, “Demands Made on General Practice by Women Before and After an Abortion,” J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 34:310-315, 1984.

20. Philip G. Ney, Tak Fung, Adele Rose Wickett and Carol Beaman-Dodd, “The Effects of Pregnancy Loss on Women’s Health,” Soc. Sci. Med. 48(9):1193-1200, 1994.

Lets listen only to the voice of God when things worsen on our side because human being can tell us anything that is good for them but not the plan of God as we know no place in the bible where there is a verse says that abort when necessary just know in life that everything that happens, happens with a reason so do not ignore that…

what if you wanted to report that someone has force someone to get abortion and you wanted to report it

If you were the person forced to have an abortion, you might speak to the police to pursue criminal charges or a lawyer to sue for some kind of monetary compensation for your pain and suffering and the wrongful death of your wanted child. But if this is in regard to someone else’s abortion, I doubt the police would listen to you and you would surely have no basis to sue in civil court.

Simple question. The references given are all from around 1998. Surely there are more recent studies and studies from other countries. Why not update the research?

There is newer research on maternal death rates, discussed in an article posted here.

You can usually find information on the latest research on our news page or at our sister site, http://www.abortionrisks.org. We have a lot of information here, stretching back years, so its a constant challenge to keep it all up to date. But these links should help you find some of the latest information.

Oops, the link to the news page above was meant to point here: https://afterabortion.org/2010/elliot-institute-news-releases-2/

This is an archived article, and just as a newspaper or journal does not generally update archived articles, we don’t try to update our archived articles. It would be very difficult to find and update every article touching on every issue raised by new research. Our more recent news releases will reference the more recent studies. We do also try to update our fact sheets.

The most comprehensive list of research articles and findings will be found at http://www.abortionrisks.org . . . but even that resource needs improvement.

“The STAKES study of pregnancy-associated deaths is beyond reproach. It is a record-based study in a country with centralized medical records. While a small number of women who died during the period investigated may have had births or abortions outside of Finland which would not have been identified in the records, there is no reason to believe these few cases would have altered these dramatic findings.”

As a Psychology student, this paragraph tells me something about this study does not ring true. (Correlation is not causation). Just because these statistics seem to fit the study, it does not mean that it is.

The last sentence “there is no reason to believe these few cases would have altered these dramatic findings” tells me that if the facts of the cases don’t add up to the study, they will ignore them.

We are not claiming that correlation proves causation.

But correlation, especially strong correlation such as in this case is strong evidence that the hypothesis that abortion reduces death rates among women is false. Similarly, it strongly contradicts the claim that mortality rates associated with abortion are lower than those for childbirth. It even provides evidence that mortality rates after an abortion are higher than for non-pregnant women.

Moreover, the Finland study published in BMJ showing a 6.5 higher rate of suicide in the year following an abortion, compared to women who deliver, supports self-reports, case study reports, and the evidence of suicide notes identifying abortion as one of the causes of suicide. So while the suicide studies do not prove causation in and of themselves (and almost no study can prove causation in the social sciences), the fact that they are consistent with self-reports indicates that these self-reports should not be dismissed as merely anecdotal. This is statistical evidence that “anecdotal” claims of suicidal behavior due to an abortion may be statistically relevant.

Also, we are claiming that the STAKES study has no self-reporting or self-selection bias. It is 100% record based. Any few cases that may have occurred outside of Finland would have had a negligible effect on the findings.

Bottom line: the Finland and California record based studies are far more reliable than past efforts, especially by the CDC, to rely solely on death certificates and newspaper reports.

For a more complete review of the literature on mortality rates associated with abortion, we strongly recommend reading “Deaths associated with abortion compared to childbirth–a review of new and old data and the medical and legal implications.”

I agree these abortion clinics should be held accountable for misinforming women that it is a safe procedure. I am post abortive did it when I was younger and now and for the last 5 years have had mental health problems that I never had before but then there’s also the emotional and physical pain. If I only knew now what they did not tell me. Those places are awful.

Dear Shanon,

I pray to God that He will help you in everything you need both physically and emotionally.

Pax tecum

for me personally i think it is completely sad that girls would do that. i